Archive

Chaahat-Chaniya Necklace

In the brilliant qawwali from Barsaat ki Raat (of 1960) written by Sahir Ludhianvi, as the competition reaches its climactic conclusion, Bharat Bhushan sings :

“Jab jab Krishn ki bansi baaji,...

View more

The Bridget Riley

View more

Kamini-Kuri

View more

Ajanta 'Guinea' Necklace

View more

Jayati 'Guinea' Necklace

View more

Priyanjana

View more

Qudratan

View more

Bonophul Hansuli

View more

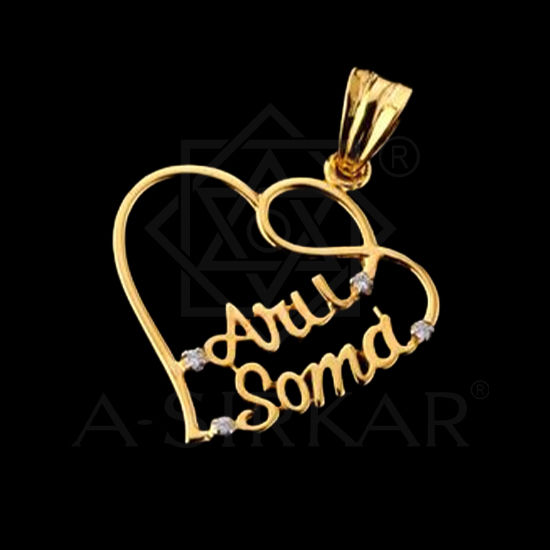

Aru-Soma

View more

Nandighosha - My New Home in Your Heart

View more

Kudrati Kanbala Necklace

View more

Jhilimili Choker-Necklace

View more

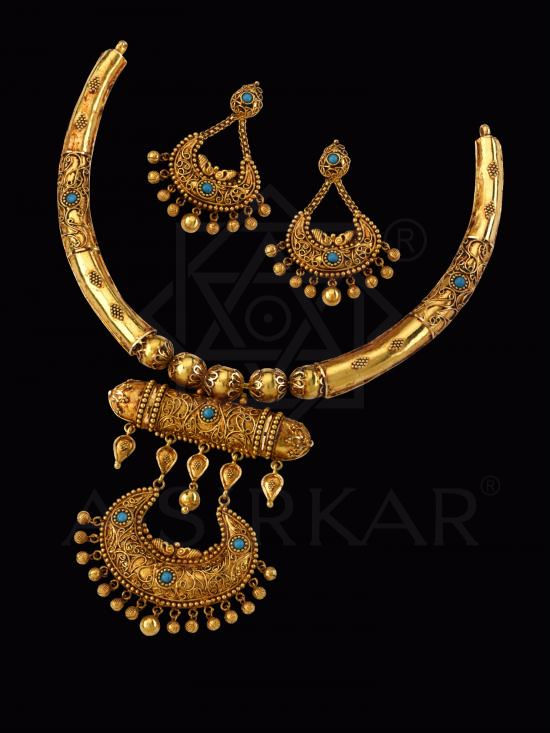

HilaalKamal

View more

Pearly Paraselene Pendant and Black Barfi Borderwala Rani-Guinea Pendant

View more

Anirneya

View more

Solapur Sita-Har

View more

SweetHearts Necklace Set

View more

Chaahat-Chaniya Necklace

View more

Ramnagarer Shonar Haathi

View more

Granny’s Lotus Belt Necklace

View more

Debangee

View more

Chandamama

View more

Vidita

View more

Manima!

View more

Nargisa

View more

Akarshini Mayur Palak Necklace

View more

Nishi Padma

View more

Nabagraha Har

View more

Benarasi Darja

View more

Deepavali Necklace

View more

Maitrayee's Love Knot Necklace

View more

Debanjali

View more

Pratul-phul Necklace

View more

Visva-Rupa KasulaPeru

View more

Pushpita

View more

Taptim Necklace

View more

Chinar Pata Pendant and Pasha

View more

Dr. Chandreyee

View more

Festival Necklace

View more

Hamak Necklace

View more

Chitrakote

View more

Chiro-Kadamphul Har

View more

Muththu-Pavalam Necklace Set

View more

Kabyasree

View more

Golden Feather

View more

Suili Mala

View more

Piyasha

View more

Moti Mahal

View more

Sutanuka

View more

Neem Chameli Necklace

View more

Ira

View more

Juna Mahal

View more

Kanakpriya

View more

The Velluri Vaddanam

View more

Padmapriya

View more

Bengal-Style Rajputi Teota Set

View more

Baurani'r DoRokha Guinea Har

View more

Kathakali

View more

Ulto Christmas Tree Necklace

View more

Omani Seahorse Pendant

View more

Tulsi Thaali Mangalyam

View more

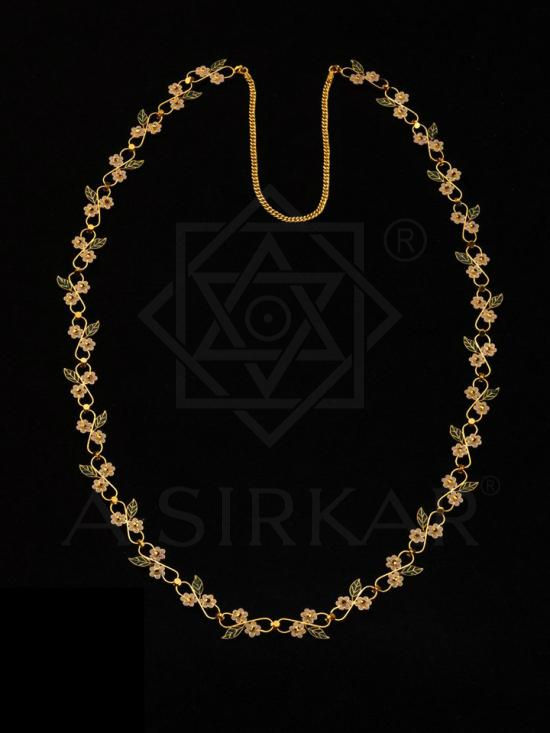

Daisy 'Love' Chain

View more

Kakoli

View more

Aabroo

View more

Tzolkin New Moon Necklace

View more

The 'Snowflakes'

View more

Nupur Jhora

View more

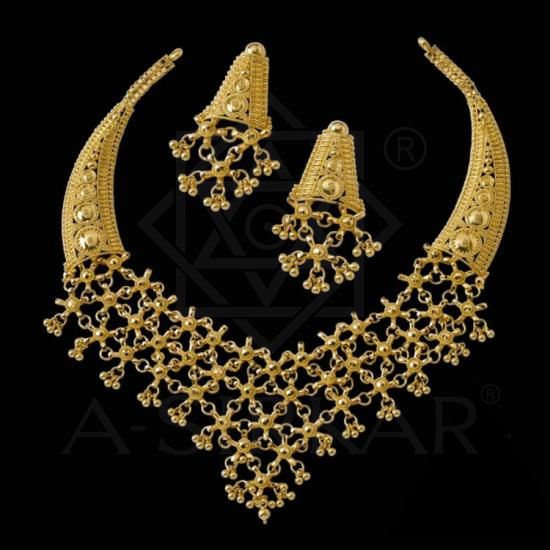

Daana Subhadra Necklace and Earrings

View more

Bichitra

View more

Bengal Rose Hansuli

View more

Sraboni

View more

Aaina Mahal

View more

Bashona Bagan

View more

Thayittu

View more

Snowflakes

View more

Panchamukhi Chatai

View more

Lajvati Necklace

View more

Kajollata

View more

Gandharaj

View more

Juin-Phul Necklace

View more

Maghreb

View more

Guinea Sonar Chand Mala

View more

Tillotama

View more

Ghagra Necklace

View more